Competition

The biotechnology industry is highly competitive and involves a high degree of risk. Potential competitors in the United States and worldwide are numerous and include pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies, educational institutions and research foundations. We compete with many of these entities who, either alone or with their strategic partners, have far greater experience, capital resources, research and technical resources, marketing experience, clinical trial experience, and research and development staffs and facilities than we do. Some of our competitors may develop and commercialize products that compete directly with our product candidates, and they may introduce products to market earlier than our products or on a more cost-effective basis. These competitors also compete with us in recruiting and retaining qualified scientific and management personnel and, in the future, in recruiting clinical trial sites and subjects for our clinical trials.

We expect any products that we develop and commercialize to compete on the basis of, among other things, efficacy, safety, price and the availability of reimbursement from government and other third-party payors. Our commercial opportunity could be reduced or eliminated if our competitors develop and commercialize products that are viewed as safer, more effective, more convenient or less expensive than any products that we may develop. Our competitors also may obtain FDA or other regulatory approval for their competing products more rapidly than we may obtain approval for any of our product candidates, which could result in our competitors establishing a strong market position before we are able to enter the market.

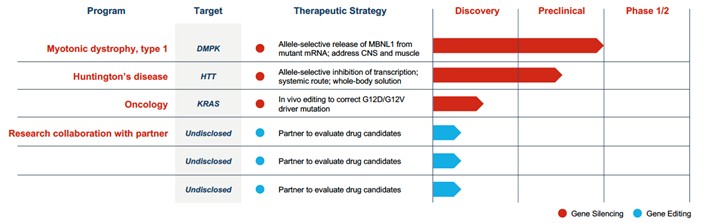

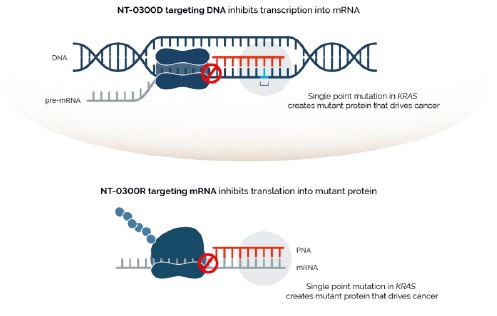

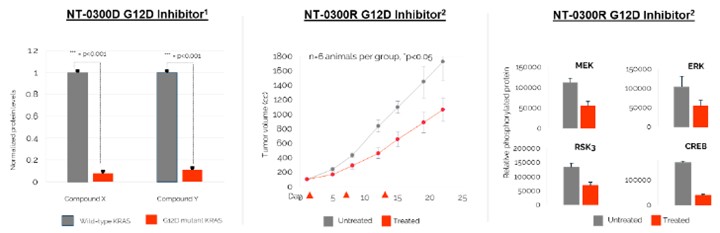

The field of gene editing is broad and characterized by a diversity of approaches. These include but are not limited to: CRISPR/Cas9 nuclease technology, alternative nuclease-based genome editing technologies such as ZFNs, engineered meganucleases and TALENs, base editing, prime editing, epigenetic editing, gene therapy, oligonucleotides, cell therapy and DNA-cutting enzymes. Based on publicly available information, we are aware of numerous companies pursing such approaches, including Arbor Biotechnologies, Inc., Beam Therapeutics Inc., bluebird bio, Inc., Caribou Biosciences, Inc., Chroma Medicine, Inc., CRISPR Therapeutics AG, Editas Medicine, Inc., Graphite Bio., Inc., Intellia Therapeutics, Inc., Mammoth Biosciences, Inc., Metagenomi, Inc., Precision Biosciences, Inc., Prime Medicine, Inc., Sangamo Therapeutics, Inc., Scribe Therapeutics, Inc., Tune Therapeutics, Inc., and Verve Therapeutics, Inc.

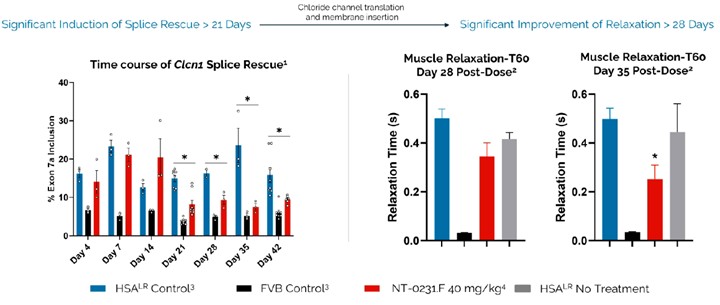

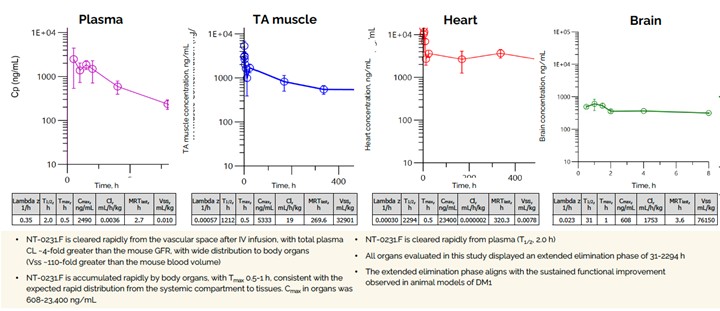

There are no disease-modifying treatments available for DM1. Based on publicly available information, we are aware of several companies actively pursuing preclinical and clinical development on various approaches to treat DM1 including AMO Pharma Limited, Avidity Biosciences, Inc., Dyne Therapeutics, Inc., Design Therapeutics, Inc., PepGen Inc., Entrada Therapeutics, Inc., Vertex Pharmaceuticals Incorporated, and Expansion Therapeutics, Inc.

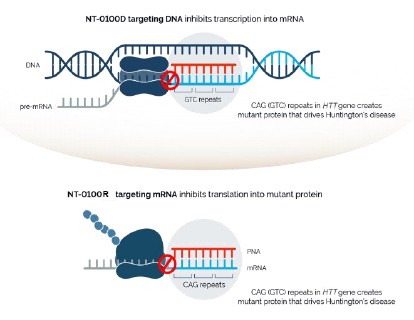

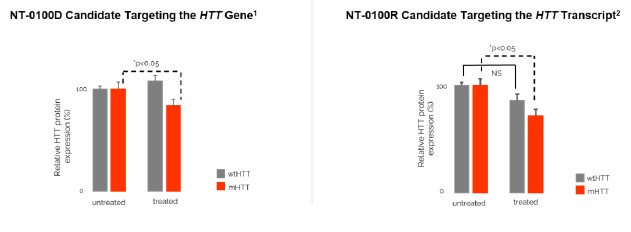

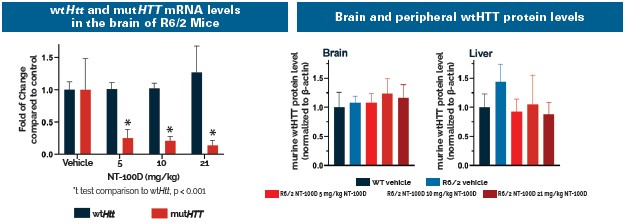

There are currently no approved treatments available to slow the progression of HD. Based on publicly available information, several companies have ongoing clinical and preclinical programs targeting the underlying disease in HD, including Wave Life Sciences, Ltd., Annexon, Inc., Sangamo Therapeutics, Inc., ProQR Therapeutics N.V., uniQure N.V., Spark Therapeutics, PTC Therapeutics, Inc., and Voyager Therapeutics, Inc. We are aware that a number of other companies are developing drugs focused on treating the symptoms associated with HD, including Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd., and Azevan Pharmaceuticals, among others.

Legacy NeuBase Pre-Merger Programs

We have an equity interest in DepYmed, Inc. (“DepYmed”), a joint venture that Ohr entered into with Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in 2014. DepYmed is a preclinical stage company focused on Wilson’s disease, Rett syndrome, and oncology applications. We also retain intellectual property, which has been licensed to DepYmed, and have no other ongoing obligations (monetary or otherwise) to DepYmed. In February 2021, the Company sold certain intellectual property to DepYmed in exchange for shares of Series A-4 preferred stock of DepYmed.

Governmental Regulation

Government authorities in the United States (including federal, state and local authorities) and in other countries, extensively regulate, among other things, the manufacturing, research and clinical development, marketing, labeling and packaging, storage, distribution, post-approval monitoring and reporting, advertising and promotion, pricing and export and import of pharmaceutical products, such as our product candidates. The process of obtaining regulatory approvals and the subsequent compliance with appropriate federal, state, local and foreign statutes and regulations require the expenditure of substantial time and financial resources. Moreover, failure to comply with applicable regulatory requirements may result in, among other things, warning letters, clinical holds, civil or criminal